dis-tutorial

Network Performance: Latency and Dead Reckoning

There are several metrics that describe network traffic. For example latency is the time it takes for a message to travel from one application to another. Latency is distinct from bandwidth, a measure of the amount of data that can be sent per time period. It’s possible to have a high bandwidth, high latency connection. An example of this is a satellite in geosynchronus orbit over which we can transmit 100 MB/sec. That’s a lot of bytes per second, but at the same time it takes 250ms for a message to get from earth to the satillite and back. Any message has to travel up to orbit at 72,000 KM and then back down, and it can never be instantaneous because of the hard lower limit established by the speed of light. There can also be low bandwidth, low latency connection, over which we can’t send very much data, but what data we do send arrives quickly. Another metric of network performance is Packet Delay Variation (PDV), sometimes called jitter. Jitter is, loosely defined, the variance of the latency. There are multiple detailed definitions for how to measure PDV or jitter, but the “variation of the latency” term captures the essential meaning. The IETF RFC in the “further readings” section discusses the issues involved in defining a precise measure.

All three of these metrics–bandwidth, latency, and jitter–effect a networked virtual environment, and if any one of the metrics is terrible it may make an NVE application behave badly. If you doubt this ask anyone who has tried to play a modern first person shooter game across a 56K dialup modem. Bandwidth is a classic measure of performance, and the “Dead Reckoning: State Updates” section discusses some aspects of this problem and how to mitigate it. The problems posed by latency are less obvious.

The latency issues can be serious in military LVC applications. They often have data feeds that originate in an austere field deployment, and may distribute data via satellite links that are inherently laggy. A deployed US Army brigade may have C4I systems in its tactical operations center linked to the rest of the world over satellite. Blue Force Tracker systems, which send individual live entity positions, also typically use satellites to transmit state updates.

Latency can create practical problems in virtual worlds, yet there are strategies to mitigate these problems. If the programmer chooses to implement them it comes at the cost of more simulation application complexity.

The Latency Problem

The essence of a virtual world is creating the illusion that application avatars from several hosts are interacting with each other in a shared virtual space. A fundamental problem that needs to be addressed is that it takes time for an entity state update to travel from one host to another.

The host publishing the entity sends out state updates through the network with the entity’s position, but it takes time for the state update to get to our host. The application that publishes the entity prepares the update message, sets the timestamp field, and then sends the message out over the local operating system’s network stack. The message must travel across the network, be delivered up the our host’s network stack, and be handed off to the application. Our application parses the message, does any local processing or computations, and updates the graphics display. That time delay–the latency–between the publisher sending the message and the receiver decoding the message and updating its own display–can cause problems when attempting to maintain the illusion of a shared world.

Latency can be a problem in many aspects of a networked simulation. Broadly speaking, latency can impact any shared, dynamic state in virtual worlds. The entity’s location is an example of this phenomenon. Someone looking at the display of a simulator, such as Close Combat Tactical Trainer, sees multiple soldier avatars, each controlled by a different host. Suppose he looks at a particular enemy solider on the display. Is the enemy soldier where our display says it is? It could be. For example if the entity hasn’t moved for the last 30 minutes it’s likely that the shared, dynamic state information for the simulation is consistent between the cooperating applications. The state updates have been sent and received long ago, and the state hasn’t changed. Both applications believe the entity to be at the same location.

But what if the solier entity is moving? The position of the avatar we see on our screen differs from what the host controlling the avatar believes the position to be. Without any latency compenstation techniques, the difference in entity position between the two hosts will be (Entity Velocity) * (Latency Time). The two hosts will see the same entity in different positions, depending on how fast the entity is moving and what the latency is.

For some applications it might not matter if the data about entity positions is not completely consistent between hosts. Even if all of them are not exactly where we think they are, the entity positions may be close enough for the purposes of the application. A map-based display for an artillery training simulator may only care if the entities are within a few meters of their displayed location. On the other hand, a virtual or augmented reality application may need the hosts to agree on the location of entities to within a few centimers. In the end, whether it matters or not depends on what the simulation is trying to accomplish.

If we know what direction the entity controlled by the remote host is moving and what the latency between the hosts is, then we can use this information to mitigate the latency problem. We can use dead reckoning (sometimes called extrapolation) of the entity’s position in our application to guess about where the host controlling the entity believes the entity to be. If the entity is traveling in a straight line at a constant velocity and our application is using a dead reckoning algorithm that models that behavior, our application may have correctly estimated the location.

Consistency vs. Throughput

There’s a fundamental tradeoff between the consistency of the shared state information and how responsive the applications are.

Imagine two applications, A and B, that implement a NVE. Each is publishing entities. It takes some time to transfer entity state information between the applications.

At first glance it might appear that we can solve this problem by insisting that all applications have the same shared, dynamic state. We’ll demand that A and B have exactly the same state information at the same time and implement some clever algorithms to make this happen. The distributed database application world loves this stuff, and they’ve developed algorithms such as distributed two-phased commits that feature atomic (all or nothing) transactions in a networked environment. The problem is that this takes time, and during that time we can’t cause still more changes to the dynamic shared state.

Let’s say application A publishes an entity position update. We start our clever algorithm for consistent shared state, such as a two phase commit (see additional reading) which involves sending an update, waiting for confirmation that application B is ready to commit the update, sending a commit request, and then waiting for a acknowledgement that the commit has occured. Notice that this requires several round trips, each of time L. Suddenly the time needed to update an entity position is several multiples of L and our state updates aren’t ocurring very quickly. What happens if the user in application A pushes a joystick to moves his entity while we are running our two-phased commit algorithm for a prior update? If we insist on completely consistent application state then our application can’t update the local entity’s position until our prior update has completed or rolled back. This is very frustrating for the user; he’s pushing on the joystick to move his entity, but the entity’s position isn’t changing because the prior update hasn’t completed. All the applications have consistent shared state, but the throughput and responsiveness is unacceptable. It gets worse if there are also applications C, D, E, and F in the virtual world, and suddenly any application updating will lock the overall world state until the update is complete.

What’s more, we may not be able to ensure a completely consistent shared dynamic state at all if we also require real time simulation. In a real time simulation the simulation has to advance at the same rate as wall clock time. If several messages need to be exchanged, each wtih L latency, we may not be able to execute the distributed transactions as quickly as the state changes occur in real time. The world can work faster than our hosts can communicate.

Yet another option is to keep the authoritative game state on a central server, which is a popular technique in commercial games. If someone shoots at someone else the interactions and physics are resolved on the central server. For various reasons (including player cheating) this can be a useful technique, but in the end it in some ways just makes the problem look different–now we have to worry about consistency between the client and the authoritative central server instead of between clients. In any event DIS made the design choice to use an entirely peer-to-peer architecture with no central server at all, so we can ignore this option in the context of DIS.

In practice, applications accept the reality that the shared states of the applications can be out of sync with each other in order to get acceptable responsiveness, or even a real time simulation that works at all. The lack of synchronized game state creates other problems we’ll discuss later.

How Bad is Latency?

Suppose our application is an interactive map that receives DIS ESPDUs and plots their position. A battlefield map may not be adversely affected at all if the entities are one second out of sync with the publishing application because the inconsistencies in the map display are trivial compared to the accuracy the application needs. Virtual simulations are much more sensitive to latency issues, and are the more challenging application to get right.

The entertainment industry has many first person shooter (FPS) games that demand attention to latency details. FPS games like DOOM, Call of Duty, and Counterstrike are popular, and players in a single game may be scattered across a continent. They have very tight, “twitch” interactions between entities, usually involving player avatars shooting at each other, and this requires low latency and high precision. Games with entities that move in a more stately manner, perhaps a naval ship combat game, may have game play that allows slower reaction times. The military training world is often closer to the later game type. Training often stresses teamwork and procedures, even in virtual worlds, rather than tasks that require fast reaction time.

How bad is latency, anyway? What should you expect for latency values?

Some military simulations are run in one room at a single site, and this reduces network latency to the minimum. Hosts that are on the same ethernet network in the same room will usually see less than 5 ms of network latency between hosts. Wireless networks can show slightly higher latency values. The latency grows as the network “distance” between the applications increases, with “distance” defined very casually. Every time a network packet crosses a switch or makes a router hop some latency is introduced. Home cable modems can add around 5-40ms, and DSL modems around 10-70ms. A dial-up modem can add 100-200ms. (Go use your stone-age technology somewhere else.) In military applications there can be other sources of latency. In an LVC environment it’s not uncommon for the state update messages to undergo multiple format changes when being exchanged between hosts. A live update from Automatic Information System (AIS) commerical ship position reports may have to have its format changed from the native AIS format to DIS, and then perhaps be converted again to XML so it can traverse a security guard that sits between the unclassified and classified networks. From there it may need to be ingested into an HLA simulation or handed off to a C4I system, and each of those has their own message format. Some military network links go over satellites in geosynchronus orbit 72,000 K above earth. The messages may be encrypted and then decrypted. Each of these steps introduces more latency in addition to the network latency.

The speed of light establishes a minimum value for network latency. A rough rule of thumb is that crossing one time zone has a minimum of around 10ms of latency. This can only increase from there, depending on the network hops taken and the efficiency of the routers on the path between the hosts.

The table below shows the observed network latency from the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California (not far from San Francisco and Silicon Valley) to several Amazon Web Services (AWS) regions where Amazon cloud servers are hosted. NPS has a good connection to high speed research networks. Non-academic sites are likely to be worse.

| Region | Latency (ms) |

|---|---|

| US-East (Virginia) | 89 |

| US-East (Ohio) | 85 |

| US-West (California) | 30 |

| US-West (Oregon) | 52 |

| Europe (Ireland) | 170 |

| Europe (Frankfurt) | 179 |

| Asia Pacific (Singapore) | 217 |

| Asia Pacific (Sydney) | 194 |

| Asia Pacific (Japan) | 144 |

| Asia Pacific (Korea) | 155 |

| Asia Pacific (Mumbai) | 294 |

| South America (Brazil) | 266 |

| China (Beijing) | 422 |

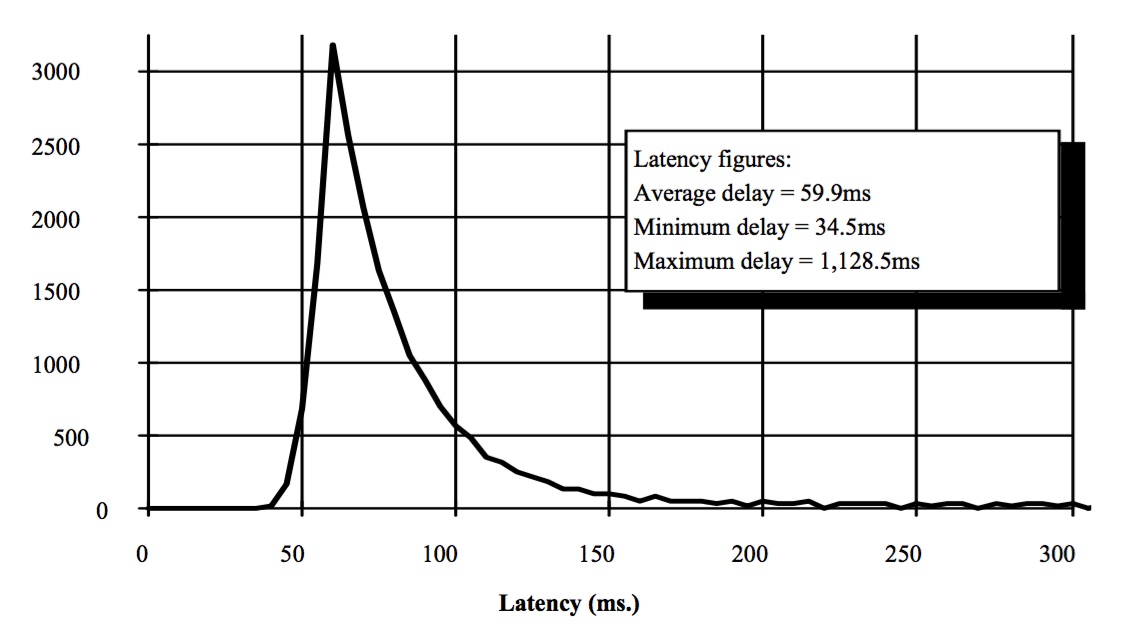

A graph displaying observed latency distribution between California and Texas (circa 2010) is shown below. The network was operating under “normal” production load, shared with production system network traffic and with no attempts to optimize via quality of service measures. This gives an idea of typical variance in the latency, and how the latency of messages is distributed.

In addition to network latency there are other sources of lag. A display frame rate of 60 frames per second is pretty good–that’s how frequently the display is updating the presentation of game state to the user. That translates into 17 ms of lag between frame refresh operations. The virutal world or other type of simulation application also performs a loop the involves receiving data, performing computations, and sending any updates required, and this inherently takes time. It may be a significant factor in latency if complicated physics, AI, or I/O such as database lookups is involved before the message can be used to update the screen.

How much does latency affect a simulation? Some estimates for the position errors resulting from various latencies are in the table below.

| Delay | Tank (100 km/h) | Aircraft (1000 km/hr) | Missile (4000 km/hr) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 | 28 m | 278 m | 1111 m |

| 85 | 2 m | 24 m | 94.4 m |

| 60 | 1.67 m | 17 m | 67 m |

| 25 | 0.7 m | 7 m | 28 m |

| 1 | 0.03 m | 0.28 m | 1.1 m |

As you can see, slower-moving entities are less senstitive to latency, and fast-moving entities more sensitive. Are the position errors big enough to worry about? That depends on the simulation, but the answer can easily be “yes.” In practice, whether a DIS virtual world simulation is “accurate” is often subjective. The objective of the simulation is often training rather than a Platonic ideal of absolute truth. If it’s convincing–if it creates a sense of presence and reality good enough for training, and if the results aren’t so far off from ground truth that negative training occurs, then it can still be useful. In the end, the users are being trained to the correct standard, even if some white lies are being told to the them. Whether this assumption about the harmless effects of simulation latency remains true may not hold for other applications, such as combat analysis or procurement decisions.

Latency and Causation

Latency can also affect perceived cause-and-effect in simulations. Suppose we have an artillery simulator, a tank simulator and a UAV simulator with inter-application latencies that are not the same. The latency between the artillery and tank simulator is 10 ms, tank-UAV latency is 20 ms, and artillery-UAV latency is 100 ms. This performance may be caused by any number of real world network architecture issues.

| Simulator | Artillery | Tank | UAV |

|---|---|---|---|

| Artillery | - | 10 ms | 100 ms |

| Tank | 10 ms | - | 20 ms |

| UAV | 100 ms | 20 ms | - |

The artillery unit fires on the tank, and destroys it. The tank simulator changes its state to show itself as destroyed, and sends out a state update. From the perspective of the UAV the tank will be destroyed before the artillery fires. The artillery fires at t=0, and the tank simulator is informed at t=10. The tank in the simulator discovers it has been destroyed and sends out an update to its state. The new “destroyed” tank state arrives at the UAV at time t=30 (or 10 + 20). The artillery simulator’s shot appears at the UAV simulator only at time t=100. The tanks explodes, and 70ms later we see the artillery that caused the explosion firing.

This is sometimes called a causality violation. It may arise from other causes in addition to steady-state latency issues. Remember, UDP makes no guarantees about in-order packet delivery, or reliability for that matter, so it’s possible for UDP packets to arrive in a different order than which they were sent.

This can mitigated to an extent, certainly if the messages are being captured and replayed. The timestamp field in the DIS PDU header can contain an absolute time hack, the time since the top of the hour. If the simulation is so configured to use absolute time stamps this can be used to order the PDUs in rough absolute time order for replay and analysis.

Dead Reckoning to Mitigate Latency Effects

Suppose we write a “Fast and Furious” themed drag racing game. Dom and Brian are in a head-to-head drag race in lanes next to each other, each driving virtual vehicles. What we want to replicate is what happens in real life, when Dom can look left and see exactly where Brian is, and Brian can look right to see exactly where Dom is.

Figure x

Figure x

What views do the simulators have of the other vehicle?

Each copy of the game has to receive a position state update from the other before it draws the opponent’s car. There’s some unavoidable latency when we send that message between the two applications. Let’s say it’s 100 ms. The player in the role of Dom looks at his display and sees this state of the game:

Dom believes himself to be a foot or two ahead. But is that accurate? Who’s really ahead? Partway into their quarter mile race they’re at 60 mph, or 88 ft/sec. In the tenth of a second it takes to get the message from Brian’s host to Dom’s, Brian’s Supra MkIV will travel about nine feet, so Brian is actually ahead by seven feet. The view from Brian’s host will place him even farther ahead. When they cross the railroad tracks at the end of the race each believes they have won, and each thinks the other should have been hit by the train. It’s also possible that Brian would choose to not use NOS because he’s so far ahead, so his incorrect view of world state changed his drag race tactics, with a bad outcome.

What to do.

The first problem to solve is getting an estimate of what the latency of the state updates is, and in DIS we can use the timestamp field to do this. Recall that the timestamp field is a measure of time since the top of the hour, and hosts typically have their time syncronized to within a few milliseconds via Network Time Protocol (NTP). See the Timestamps section for details. When we receive the state update message we can examine the timestamp field and compare it to our own host’s time; the difference between the two is an estimate of the total latency between the hosts.

If we have an estimate of the latency between participants we can then run a dead reckoning algorithm. In DIS the DR algorithm to use is specified by the application sending the state update, so the application simulating Brian can choose what algorithm should be used. DIS DR algorithm number five is probably a good choice; it includes both velocity and acceleration in the DR computations, and ignores angular velocity. So the Brian application can specify that midway through the drag race he is traveling at 60 mph and accelerating as well.

When Dom’s application receives the update it now has an estimate of the latency, a DR algorithm, and parameters including position, velocity and acceleration. Dom’s application can use this to draw Brian’s car where it thinks it is. Instead of just the position contained in the state update, Dom’s application will use the latency, velocity, acceleration, and specified DR algorithm to draw the Supra some distance ahead of the reported position. Now Dom is less smug about his status in the drag race, and this is a good training effect.

Note that we are now using DR for a reason distinct from decreasing bandwidth use; it’s being used to mitigate the effects of latency. This isn’t cost free; running the DR algorithms for both the entities being received and the entities we publish can consume some computational resources. But in the end, most modern CPUs have several cores, and these tasks can often be parallelized. Simulations are often not restrained by their ability to do computations, but rather by graphics or I/O.

Solutions

One emerging method for coping with latency is to make distributed networked virtual environments less distributed. That sounds contradictory, but isn’t, quite. Cloud computing has compelling business advantages over conventional approaches and promises significant cost savings. Virtual machines in the cloud can be run very cheaply. There are also applications like Remote Desktop on Windows, X-Windows or VNC on Unix, or Apple Remote Desktop in the Apple environment that let the user remotely view the desktop of a machine running elsewhere. The conventional approach to distributed simulation is to keep the both the participating hosts and the displays local to the user. If the simulation is geographically distributed this also means the latency can be high between the hosts running the simulation, and therefore the local application physics starts becoming complex. But if the hosts running the simulation are co-located on the cloud then the latency-induced location errors are smaller, because latency between hosts is reduced to the bare minimum. This of course is pushing the problem around on the plate rather than actually solving it, but it may rearrange it in a way that’s useful. The user is now seeing what is in effect a streaming video of the desktop that’s running on the cloud. All his user input–his mouse clicks, his keyboard input, his joystick inputs–are going from his local desktop to the cloud, latency time L away, which means his inputs are less responsive. The video of the desktop running in the cloud has to be sent back to the local desktop, which takes time and makes the display less responsive. We’ll also probably need more bandwidth to communicate with the server; we’re streaming back the video display instead of sending state updates, and the state updates tend to be smaller. The tradeoff is that it may make the physics workable in high latency distributed applications.

Summary

That’s a lot of problems, and not a lot of solutions. It’s the nature of the beast. Do what you can to keep latency low. Conventional wisdom in the commercial gaming world is that FPS games should have under 100ms of latency. Human reaction time is around 250ms; if your simulation is trying to do human-in-the-loop, twitch reaction training it can’t be much higher than that. High latencies can be gotten away with for certain types of applications that don’t need exactly current state. It doesn’t matter much if an entity position is 5 m out of date if it’s also on the receiving end of an MLRS battery attack. In a high latency environment simulation designs can try to de-emphasize the reaction time component of training, and emphasize things like teamwork or training for procedures that rely less on reaction time.

FURTHER READING

Sandhep Singhal and Michael Zyda, Networked Virtual Environments, Addison Wesley 1999. It’s a very good book that discusses many of the fundamental problems in virtual worlds.

Andreas Tolk, Combat Modeling for discussion of causation and drag racing

Two-Phased commits: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Two-phase_commit_protocol

Game latency: https://web.cs.wpi.edu/~claypool/papers/precision-deadline-mmsys/claypool-precision-deadline.pdf

Packet Delay Variance as discussed by the IETF: https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc5481

Cloudping, a tool for finding the average latency to AWS regions: http://cloudping.mobilfactory.co.kr/

An MS thesis devoted to measuring latency in DIS from Captain Drinkwater at AFIT: documents/DISLatencyThesis.pdf