dis-tutorial

Dead Reckoning: State Update Frequency

Dead reckoning is a technique that can make informed guesses about the location of entities, and this can reduce network traffic. Dead reckoning can also reduce the impact of message latency.

Imagine an entity moving in a straight line at a constant velocity. The entity is owned by one particular simulation in a networked virtual environent. Its state–for example, its position–is changing, and we need to inform other participating simulations in the NVE about the change in dynamic state information. In addition it takes time for the state update to be sent from the application that controls the entity to our application.

The entity is experiencing constant changes to its shared, dynamic state. How can we make the other participating simulations closely match the entity’s state as it changes?

Why

Notice that there are two basic problems that are addressed by dead reckoning: how frequently we receive state updates, and network message delivery latency. The latency aspect is addressed in another section, while this section addresses state update frequency.

State Update Frequency: Brute Force & Ignorance

A simulation participating in a NVE strives to match its visual display to the that of the simulation’s other participants. The simulation that owns the entity discussed above sends out updates, but those updates occur at discrete time intervals. If they are sent once a second and we use no other measures to hide this fact on the receiving side, that means the entity’s position in other applications will appear to do “hyperspace jumps” from the old position to the new position every second–if the entity’s postion has changed by 10 meters in one second, the entity may appear to move in 10 meter jumps, once a second. This may or may not be significant, depending on the circumstances. Large hyperspace jumps are distracting if the application is a virtual environment, where the sine qua non is the creation of a sense of realistic, shared presence. If the entity is moving slowly and the hyperspace jumps are small the user might not even notice them. If the application is a map-based and the scale of the map is large enough the user might not be distracted by position jumps of even hundreds of meters. In addition users of map applications have more forgiving expectations about display update changes; the hyperspace jumps on a map don’t take them out of the sense of presence in the way they would if they occurred in a virtual environment. As programmers we can exploit the low expectations the users have of map displays. In the end, the significance of the simulation’s display update rate depends on the training objectives of the simulation and the expectations of the users.

Still, in many applications, particularly virtual environments, we want to limit the update frequency artifacts apparent to the user. For our entity moving in a straight line at a constant velocity one possiblity is for the simulation that owns the entity to simply send out more frequent updates. Instead of sending out a update for the entity’s position once a second, we can send out updates once every 30th of a second, and the entity will be animated more smoothly. There are some drawbacks to this approach.

First of all, bandwidth. We have just increased the bandwidth used for updates for each entity by a factor of 30. This might not be terrible in some instances. In DIS an entity state PDU has a minimum payload of 144 bytes plus 28 bytes of network overhead, so our bandwidth use increased from 172 bytes/second to over 5K bytes/sec. This isn’t so bad in a typical wired network that has 100 mbit/sec ethernet, but if a NVE has a thousand entities it starts to become a factor. It’s also a factor if we are using DIS as a constructive simulation protocol for a corps-sized unit with thousands of entities.

There are more serious and subtle problems with the brute force approach than just bandwidth use. A network’s performance is a multi-dimensional optimization problem, and NVE state updates are often in a format that are by their nature problem-causing for the network as a whole. State updates are often conveyed via UDP, and are small and frequent. That’s about a worst case situation for UDP socket clients and isn’t that good for the network’s performance. An application receiving many small UDP messages often reaches practical limits well before the network’s theoretical maximum bandwidth is reached.

Receiving a UDP packets at a high rate is a computationally time-consuming affair. Deep in the operating system the network interface card will raise interrupts that need to be handled by the CPU and operating system, and as of this writing a realistic maximum is about 50,000 UDP packets per CPU core. Our 30,000 updates per second outlined above is starting to bump up against that, and as a result we’ll probably see some dropped UDP packets. We can get better throughput if we bundle several PDUs into one UDP packet to send fewer, larger UDP messages (see the section on PDU bundling) but this also means the average latency of the updates is increased. The bundling approach requires that we wait for several update messages to fill an outgoing queue before we have enough to bundle and send.

The brute force approach also means we have to decode more packets and do the processing associated with applying the updates to the system, and this increases CPU load. When going from one update message per second to 30 per second we now have to decode an extra 29 messages per second, which usually involves memory copies and other operations. In production virtual environments the designers often have CPU budget allocations for different aspects of the system–so much for AI, so much for graphics and physics, and a much smaller amount for network operations. Networking will almost always get the short end of the stick in budget allocation debates because designers would rather spend the cycles on spiffy in-game physics rather than parsing network messages.

For all these reasons a pure brute force approach is not realistic for anything other than small virtual environments. It can have its place, but in larger NVEs it’s not a practical approach.

Dead Reckoning to Reduce Traffic

An alternative approach for our hypothetical entity moving in a straight line is to use dead reckoning to make guesses about the location of entities. If we send state updates once a second we can, on the receiving side, interprolate the position of the entity based on its velocity. The DIS entity state PDU includes a field for entity velocity, so the most recent ESPDU received has enough information to allow us to calculate this.

We receive an update at t=0 for an entity moving north at 10 m/s (a little over 20 mph). At a frequency we choose–perhaps 30 per second–we can run our dead reckoning algorithm to guess where the location of the entity is. In our case, we will move the entity 0.3 m north, about a foot, at every tick of the algorithm. The math in the DR algorithm is fairly efficient, at least more so than the other alternative, receiving and processing UDP packets.

This is all fine and good. But this all assumes that the location and velocity alone provides a pretty good guess for where the entity is located between receiving state updates. What if that’s not such a good guess? What if the entity is accelerating, for example? What we want is several different algorithms that can provide different approaches for making guess depending on the nature of the entity’s behavior. DIS entity state PDUs allows the owner of the entity–the applicaiton sending updates–to specify what algorithm the receiver should use. The owner of the entity usually has excellent information about what DR algorithm is reasonable, and the DeadReckoningParameters record of the Entity State PDU contains an “deadReckoningAlgorithm” enumeration field. When the application that owns the entity puts out a state update it specifies what DR algorithm recipients should use, and includes the information needed, such as velocity and acceleration, in the PDU.

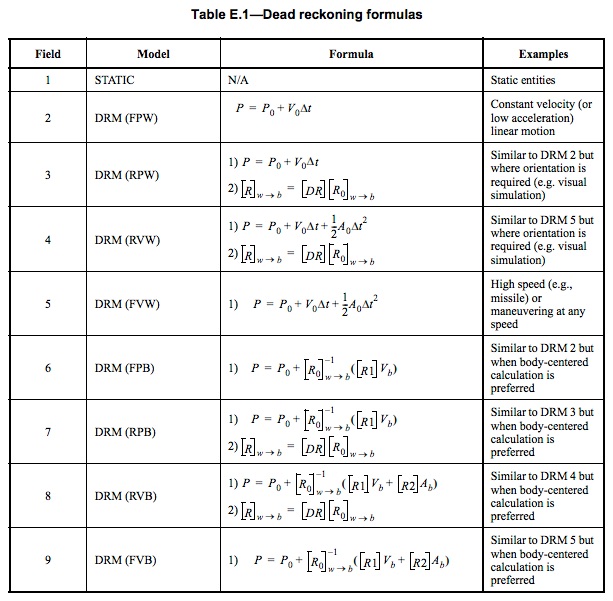

The values in the table below map to the alogrithm to be used. For example if the PDU specifies DR algorithm 2, the recipient should use simple velocity-only DR.

DeadReckoningAlgorithms.jpg</img>

DeadReckoningAlgorithms.jpg</img>

If the value “1” is seen in the field, the entity should not be dead reckoned at all. Dead reckoning is not computationally free, and if the entity is not moving it makes sense to tell the receiver to simply not perform the computations.

Dead Reckoning algorithms 2 through 5 are mostly straight forward applications of Newtonian mechanics.

DR algorithm two uses only velocity to guess the location of the entity. DR algorithm three expands the kinematic information used in DR to angular velocity, which allows the receiver to guess the entity’s orientation as well. DR algorithm four expands this further to linear accleration. DR algorithm five uses linear velocity and acceleration, with no angular components.

A Perfect Circle

As mentioned in the previous section, Dead Reckoning algorithms 2 through 5 simulate Newtonian mechanics, i.e. an inertial reference frame, and algorithms 4 and 5 include a term allowing for up to constant acceleration. With this constant acceleration, one can at best simulate a parabolic trajectory, or with repeated Entity State Updates a piecewise parabolic trajectory. But what if one would like to simulate a coordinated turn where the entity travels in a perfect circle? That is where DR algorithms 6 through 9, which use the local, body-centered coordinate system rather than the global coordinate system, come in handy. In particular, DR algorithms 7 and 8, which allow for a rotating entity, can be used to simulate a circular path.

In order to use the Dead Reckoning algorithms to describe a circle, first consider a flat turn (roll = 0). The body angular velocity omega_z, and also the Euler angle heading rate, for a circle with a given radius traveled at a given speed is omega_z = dheading/dt = speed/radius (radians per second). In body coordinates, the velocity V_b when traveling in a perfect circle is (speed,0,0). Furthermore, for the body-centered Dead Reckoning algorithms we choose the “acceleration” A_b to be the derivative of the velocity in body coordinates V_b. Since V_b is constant for a perfect circle, A_b will be identically zero for this case. Note that this derivative A_b is not generally equal to the entity acceleration expressed in body coordinates a_b. See the Towers & Hines paper for further discussion.

Now that we know how to simulate a flat turn, one may think that it is a simple matter to simulate a banked (roll != 0) turn by setting the roll to a constant non-zero value. In the case of a banked turn the heading and heading rate are still the same as for a flat turn, but now the roll is assigned a constant non-zero value, and the corresponding roll rate is still zero. The convention for roll is positive tilt to the right (also called right wing down), so for a clockwise turn we expect the roll to have a positive value, and for a counter-clockwise turn we expect the roll to have a negative value.

However, the angular velocities in the Entity State PDU fields are not the derivatives of the Euler angles heading, pitch, and roll; rather they are angular velocities about the the body x, y, and z axes. The distinction between Euler angle derivatives and body angular velocities is explained in IEEE Std 1278.1, which also contains formulas allowing one to convert from one to the other. Applying the angular velocity formula to the case of a constant roll banked turn in a circular trajectory (by associating psi, theta, and phi with yaw, pitch, and roll respectively), one finds that omega_y and omega_z are related to the heading rate calculated above for a flat turn, by multiplying by the cosine (omega_z) and sine (omega_y) of the bank/roll angle. For a clockwise turn, omega_y and omega_z will be positive; for a counter-clockwise turn omega_y will be positive and omega_z will be negative.

Note that the derivation of the body-centered Dead Recknoning algorithms involves integrals of matrix exponentials. Although matrix exponentials can be represented as infinite series or matrix, the specific integrals needed by these DR algorithms can be evaluated exactly by summing only a few matrix terms as specified in IEEE Std 1278.1 and derived in the Towers & Hines paper. In other words, the simple matrix formulae in in IEEE Std 1278.1 are exact closed-form evaluations of the integrals, and as stated in the Towers & Hines paper: “With either choice of second derivative, a_b or A_b, the appropriate version of Algorithm 8 will propagate a coordinated circular turn indefinitely without error. With our choice of send order translational derivative, A_b = 0 for a constant speed circular turn (assuming the only orientation changes are due to performing the turn), and so Algorithm 7 can be used.”

Dead Reckoning Thresholds

One of the interesting insights of DIS is that the owner of the entity can change the DR algorithm used, and is also not limited to sending out updates only at fixed intervals. If the owner of the entity realizes that the receivers will be out of sync with the owner it can immediately send an entity state PDU with the current entity state information. Let’s say our tank makes a left turn. The owner knows that the receivers have been told to DR the entity as moving in a straight line with the given velocity. Rather than waiting for the next heartbeat message to send out a state update, the owning application can immediately send a new ESPDU when the turn is made. This will minimize the time the receiving applications are out of sync with the owner.

The idea of sending out updates when we know the simulations listening to our updates will become out of sync can be generalized. We know what DR algorithms other participants are using–our simulation told them what to use. We also know what data we sent them, so we know enough to compute where they think we are. So a technique is to run the dead reckoning algorithm on our host as well–we’ll do exactly the same computations as the receiving simulations. When we discover that the dead reckoned position exceeds some specified threshold compared to where we know the entity is, we send out an immediate state update.

What If the Dead Reckoning is Wrong?

Obviously, the DR algorithm could fail. One participant could let off the gas. This will likely trip the DR threshold and cause an update message to be sent, but it will still take some period of latency before it arrives at the other host. During this period the other host will continue to DR and update the screen position of the Humvee, which will show us a false position.

So what do we do in this case? Basically, we lie to the user. A key part of virutal worlds is keeping the user immersed and providing him a sense of presence. When we discover the local DR algorithm has incorrectly placed an entity, the usual approach is to gently correct the position of the entity to the latest reported position. The key is to make the movement look realistic. This preserves the virtual simulation’s sense of presence, even if the entity’s position is not immediately and exactly corrected.

Summary

Dead reckoning is a useful technique that can reduce the number of state updates sent on the network. Instead of trying to animate entity movement using only state updates, we can instead use DR. This reduces the traffic, and reduces the CPU load on the simulation participants, and may well reduce the number of UDP packets dropped by the network.

###Further Reading:

Bandwidth benchmarking: http://wiki.networksecuritytoolkit.org/index.php/LAN_Ethernet_Maximum_Rates,Generation,_Capturing%26_Monitoring

UDP internals: https://www.codeproject.com/articles/275715/real-time-communications-over-udp-protocol-udp-rt

UDP Linux internals: https://blog.packagecloud.io/eng/2016/06/22/monitoring-tuning-linux-networking-stack-receiving-data/#data-arrives

Performance tuning: https://blog.cloudflare.com/how-to-receive-a-million-packets/

Dead Reckoning performance: documents/DeadReckoning_Ryan.pdf